It's the NGDP, Turkish Edition

The CBRT's inability to reduce inflation despite high rates leads some to argue that conventional policies do not working. Some economists argue that inflation is caused by greed. Both are wrong.

Edit: Scott Sumner has a coverage of this post at Econlog. I’d urge you to read it as well!

After the 2023 elections, Turkey abandoned its infamous NeoFisherian interest rate policy (which Erdoğan formalized as "interest is the cause, inflation is the result"), and adopted a more conventional policy with a new Central Bank head (who was recently fired). As of February 2024, Turkey's interest rate is at 45%, and inflation increased to 64.8% in December. Meanwhile, the Turkish lira reached a new record low against the US dollar in early January, trading at over 30. Inflation has become the central pillar of a Turkish person's life, and this is not likely to change soon:

The institutional weaknesses in the Turkish economy and how Erdogan's policies have plunged the economy into a deep crisis have been extensively covered before, so I will not focus on them in this post. Rather, I will discuss a new (and extremely (!) original) theory produced by some Turkish economists in response to the fact that inflation is still not under control despite high-interest rates.

Is Greedflation in The Room with Us Right Now?

Mahfi Egilmez, a relatively popular left-of-center economist in Turkey, recently discovered the concepts of greedflation and shrinkflation and decided to use them, claiming that there is a "greedflation problem" in Turkey. For those unfamiliar with these terms, greedflation refers to an accelerating high inflation situation where “firms are taking advantage of high inflation periods and raising prices out of greed, to increase their profits.” Greedflation was previously used by some economists and in the media to explain 2021–2023 American inflation, but it was proven wrong. Or there was an idea floating around that Beyoncé’s concert in Stockholm increased inflation in Sweden.

Egilmez claimed that "under the same conditions, the all-inclusive hotel offered a price of 35,000 Turkish Lira last year and 111,000 Turkish Lira this year. If inflation is 65%, this is greedflation.” Egilmez also claims that there are "skimpflation" (reducing the quality of the product) and "shrinkflation" (reducing the weight of the product) trends in Turkey. Unfortunately, he does not consider how average costs for companies may have changed. President Erdogan has also accused supermarkets of being the source of inflation because they "greedily" raise prices in the past. Here’s Joey Politano:

When the federal government spends deficit-financed money it definitionally increases the surpluses of the private sector. In other words, when the government borrows and spends money that money has to go to private sector actors (businesses and households) who see a corresponding bump in income. The rise in corporate profits is largely attributable to this increase in spending: money first went from the government to households in aggregate, and now those households are spending money and sending it to corporations in aggregate. The jump in aggregate corporate profits is no more responsible for the rise in inflation than the prior jump in household income.

Just as rising profits are not the cause of inflation in the USA, it is not the cause of inflation in Turkey either. The increase in corporate profits is not the source of inflation; if it were, we also should have blamed consumers for raising inflation because they consume too(which I don't think anyone would claim). For those who turn their heads to fiscal policy to blame, it must be offset by monetary policy, so even fiscal policy is not the “source” of inflation.

An economist should have considered how the average costs of companies had changed and how this is affected by the Turkish lira being at a record low level, before arguing that there is greedflation just because they looked up a chart and saw that profits almost doubled in local currency(in a period that Turkish lira's value decreased 121% against US dollar). However, even seemingly prominent economists seem to have forgotten our basic economic principles.

I propose to look at inflation from a different, but not an original perspective. The advantage of this perspective is that it includes an analytical attitude rather than approaching economic problems from a populist or emotional standpoint. It provides a simple, clear, and consistent perspective:

Let's imagine that a material(gold, silver, cigarette boxes, or government-issued papers) is accepted as a medium of account by the general society, which we call money. Money is produced by an institution called the Central Bank. Now let's assume that the individuals in this society prefer to hold 1000 units of currency each. Nothing less or more. Again, let's assume that the output is in equilibrium in the long run.

Now let's assume that the Central Bank has started to increase the money supply at a rate such that each individual in society holds 2,000 coins, not 1,000. This causes households, to hold more money than they would prefer, even if their income remains unchanged in real terms (that is, even if they do not become richer in a real sense). People want to spend their excess money on various goods and services. With too much money chasing too few goods, individuals providing the supply of goods or services will inevitably make more profits(again, in nominal terms). However, since all individuals want to dispose of their excess money, the prices of goods and services will have to increase to the same extent. Thus, economic equilibrium returns to its previous position, only with a higher price level.

The thought experiment above depicts the effect of a one-time increase in the money supply in a closed society. The real world is much more complex, but we cannot reason about real-world inflation without properly grasping the implications of our hypothetical experiment. In a scenario where the Central Bank would constantly increase the money supply, economic actors would react by adjusting their consumption or production, and prices would change according to their expectations. An economic actor who thinks that his currency will lose value and the average cost of the goods he produces will increase, and that this situation will not improve soon, increases prices by thinking not only of today but also of the future. There's no greedflation mystery, only rational expectations.

A similar case arises in the event of scarcity. It is not only defendable but also desirable for companies to raise prices in response to shortages. The alternative to letting the price mechanism align supply and demand is to rely on something worse, such as rationing. When the government limits rent increases to 25% the only thing the market can do is increase initial rents. Considering the stickiness of the housing market, landlords increase the rents of their new houses to align the five-year rental price according to inflation expectations(at the end of the fifth year, the landlord can apply to the court and ask the judge to determine the rental price to be applied in the new lease year). The consequences of rent control have been extensively discussed in basic economic courses and textbooks, but rather than accepting the consequences of flawed policies, Turkish policymakers and economists blame the "greedy" landlords.

Never Reason From an Interest Rate Change

CBRT has increased interest rates steadily since May 2023. Even though interest rates are at 45% today, inflation has not been brought under control. This has led some to argue that conventional economic policies do not work. However, those who make this claim frequently fall into the fallacy of reasoning from interest rate changes.

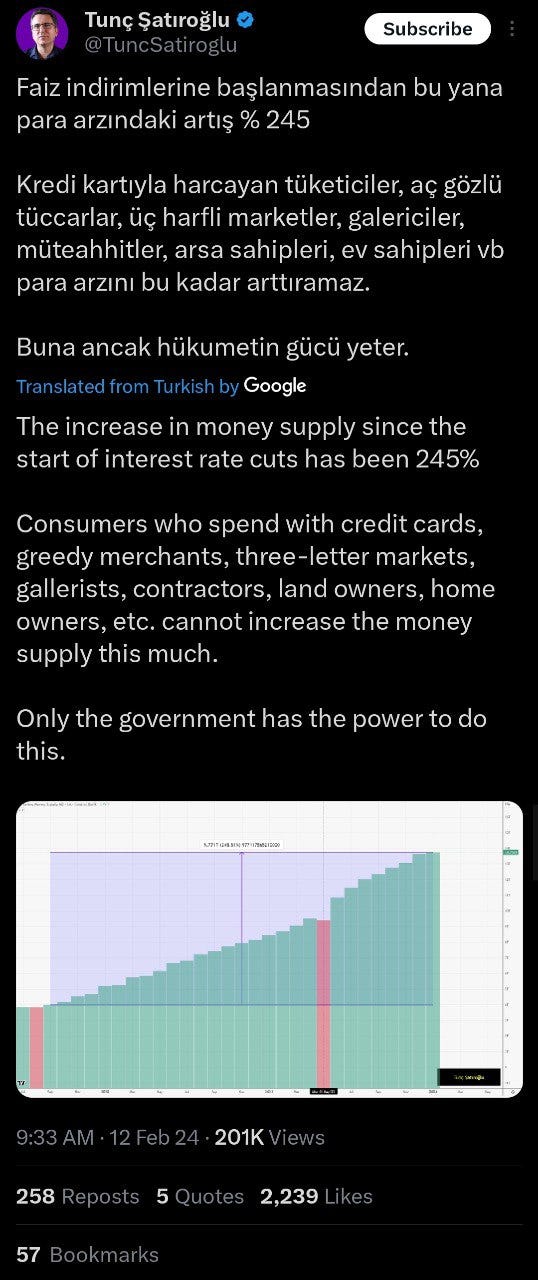

Tunc Satiroglu points out that there has been a 245% increase in the money supply since the CBRT started interest rate cuts in 2021:

You might have high-interest rates and high inflation. This is just a phenomenon we see when the Central Bank falls behind the natural equilibrium rate. From a natural rate perspective, the explanation for why inflation is not lower is that policy interest rates increase, but the natural interest rate increases faster.

This is exactly why Argentina is experiencing hyperinflation while having interest rates over 90%. One cannot argue that the conventional monetary policy did not work in Argentina and Turkey, because those countries did not start to implement conventional policies at all. If Central Banks want to create inflation, they have every tool to do so and they can create it whenever they want. When policy does get tight, the effects will be almost immediate. CBRT simply refuses to take the necessary steps to do so.

Note that determining the natural rate of interest is a challenging and complex issue. Moreover, economists measure the R-star differently and often disagree on what it even is:

Of course, it’s very difficult, because to use these structural techniques, one has to be sure that the structure of the economy is correctly specified. And we, macroeconomists, know that we rarely understand the structure of the economy correctly, and so it’s quite difficult to know what R-star is. In practice, this is going to lead to real issues. And so— I actually saw this tweet from you, David— different measures of R-star disagree now, or at least when you tweeted, by something like 200 or 300 basis points, like really big amounts. Some measures of R-star say we’re in the low-interest rate world, some say we’re in the high-interest rate world. And so there’s a theoretical lure to R-star, but in practice, when we try to measure it, [it’s] really difficult to do so. And so, that one challenge is just that the point estimates disagree a lot between these different structural models. A second one would be nerdier, but I think equally important, which is that the standard errors associated with these estimates are giant.

So, the last time I checked the Laubach and Williams measure, it spans something like the 95% confidence interval span, something like five or six percentage points of interest rates, really big amounts. Now, again, I don’t mean to be mean-spirited. I think it’s a crucial object to measure and these people like Laubach and Williams, and successors like Lubik and Matthes, but, you know, really breaking the frontier. What we wanted to do is see if we can come up with different measures to come out of that. So, that’s the preamble, why we should care about R-star.

These standard errors make the R-star a poor indicator for determining the stance of monetary policy. How can these models guide us when economists don't agree on where the natural rate of interest is, or even can't agree on what they are trying to measure? While many central banks target short-term interest rates, they do so not based on R-Star models, but rather on a wide range of data such as macro data and financial market data. It’s nothing more than wading through the dark with a flashlight.

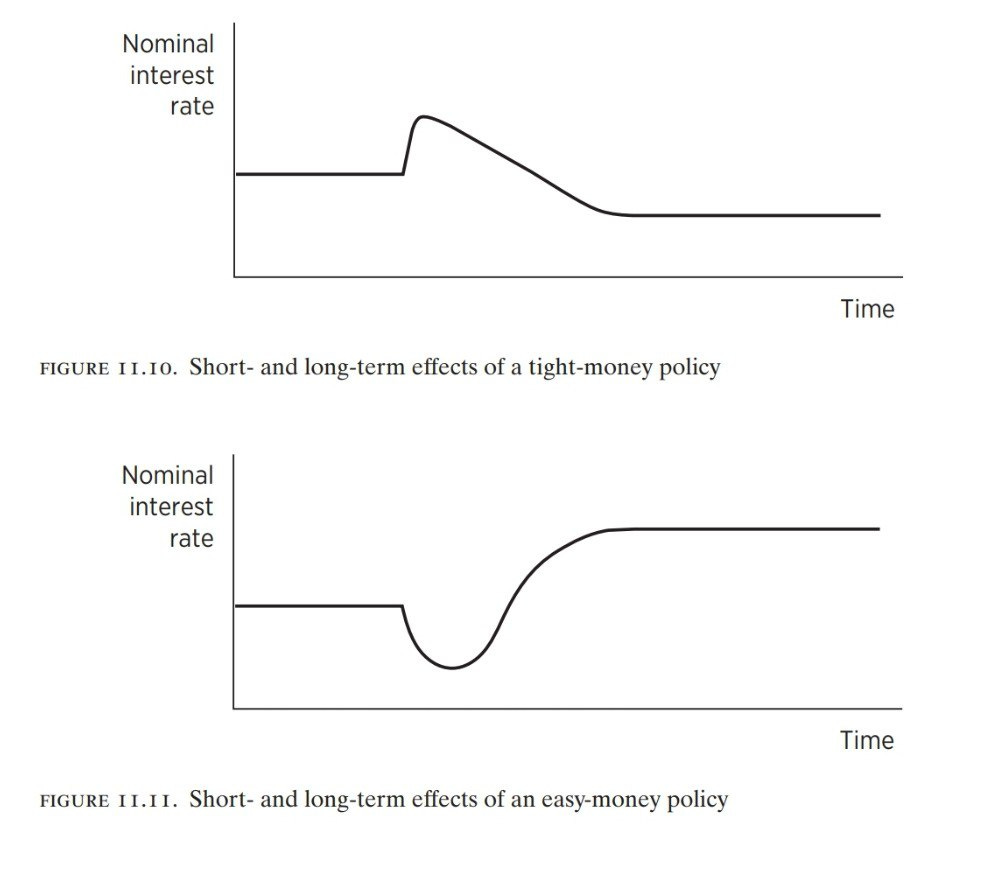

Fortunately, there is a better explanation: the Fisher effect. An expansionary monetary policy leads to higher inflation expectations, which in turn leads to higher interest rates. As Milton Friedman and Scott Sumner point out, low-interest rates might indicate that monetary policy was previously tight, whereas high-interest rates might indicate that monetary policy was loose1:

High interest rates in Turkey might be also the effects of the expansionary policy experienced in previous periods. However, the media and economists ignore the Fisher effect and think that high interest rates represent a tight monetary policy. Whether this is an effect of previous periods of loose money or truly tight monetary policy is a question that is often ignored. The answer might give us an idea about the stance of monetary policy, but it is not easy to determine.

Satiroglu correctly states that "consumers who spend with their credit cards, greedy merchants, supermarkets, and landowners cannot increase the money supply, only the government can." However, M2 is also not a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Satiroglu makes the correct interpretation by looking at the wrong indicator.

There are problems with 1970s-style monetarism, which interprets the stance of monetary policy with M2. But there are worse ideas than classical monetarism and one of these ideas is the indicating the stance of monetary policy by using interest rates. Since high interest rates do not always mean tight money and low interest rates do not always mean loose monetary policy, and even R-Star cannot be a useful indicator, interest rates cannot be a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy at all. We must abandon it when interpreting the stance of monetary policy. In an ideal world, I would also like to see central bankers stop targeting interest rates.

When in Doubt, Look at NGDP

So, Kursad, what indicator should we use to evaluate the stance of monetary policy, given that M2 and interest rates, or even the inflation rate, are not useful indicators and greedflation is simply a fanciful idea? As I have mentioned often before on this blog, everything becomes clearer when you look at the world from the perspective of NGDP, not from the perspective of interest rates or price changes. By focusing on NGDP growth instead of inflation, greed, or interest rates, we can improve the evaluation of the economy.

Why is NGDP important? Because it is the total value of income in the economy in terms of currency. Most contracts in our economy are signed on nominal terms. So NGDP is a useful metric for measuring people’s ability to fulfill nominal contractual agreements. If there is a serious decline in NGDP, the country will face a serious debt crisis.

NGDP is more of a “real” thing; it is not just the sum of RGDP and inflation, it has real effects. As I have argued before, NGDP is an important indicator of everything we care about in an economy:

1) recessions and employment fluctuations are highly correlated, 2) nominal shocks have real effects, 3) hourly wages closely follow NGDP/person, 4) when the economy is hit by a negative nominal shock W/NGDP becomes highly countercyclical because nominal wages are sticky 5) W/NGDP is especially useful in explaining employment fluctuations, hence the recessions.

Now, we have a good indicator of the stance of Turkish monetary policy. When looking at the NGDP growth data, it seems CBRT did not take a single effective step to tighten monetary policy:

Note the NGDP growth trend before 2018. Under Erdogan’s command, CBRT has adopted a recklessly expansionary monetary policy, and this continues at full speed. Far from being able to bring inflation under control, CBRT refuses to take a single step forward. This is even more clear when we look at it annually:

Here, one might say that real growth is unstable in countries like Turkey. This is indeed true: in contrast to the stable real growth trend of developed countries, we can often observe unstable real growth trends in developing countries. NGDP per capita instead of NGDP may give a better idea in interpreting the stance of monetary policy in this case. But it tells the same story. NGDP per capita rising at an incredible pace is never a good sign. The CBRT can raise interest rates as much as it wants. There will be no point in that if it does not show that it is determined to control NGDP and promise to be responsible.

Don’t let illusive concepts of inflation or interest rates, greed, etc. distort your understanding of the economy, and focus on what really matters: NGDP growth. In the end, it’s always the NGDP.

P.S.: If you want to watch a video on the course of the Turkish economy and hyperinflation, Sandro Sharashenidze got you:

P.P.S.: Refet S Gürkaynak, Burçin Kısacıkoğlu, and Sang Seok Lee Author recently published a paper on the exchange rate and inflation under Turkish monetary policy. I will cover the paper in a later blogpost, but here’s the abstract:

For the academic audience, this paper presents the outcome of a well-identified, large change in the monetary policy rule from the lens of a standard New Keynesian model and asks whether the model properly captures the effects. For policymakers, it presents a cautionary tale of the dismal effects of ignoring basic macroeconomics. In doing so, it also clarifies how neo-Fisherian disinflation may work or fail, in theory and in practice. The Turkish monetary policy experiment of the past decade, stemming from a belief of the government that higher interest rates cause higher inflation, provides an unfortunately clean exogenous variance in the policy rule. The mandate to keep rates low, and the frequent policymaker turnover orchestrated by the government to enforce this, led to the Taylor principle not being satisfied and eventually a negative coefficient on inflation in the policy rule. In such an environment, was the exchange rate still a random walk? Was inflation anchored? Does the “standard model” suffice to explain the broad contours of macroeconomic outcomes in an emerging economy with large identifying variance in the policy rule? There are no surprises for students of open-economy macroeconomics; the answers are no, no and yes.

Sumner, S. (2021). The Money Illusion: Market monetarism, the Great recession, and the Future of Monetary Policy. The University of Chicago Press.

The US version:

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/a-simpler-view-of-monetary-policy